*This article was also posted on the The Gender Policy Report at the University of Minnesota’s Hubert H. Humphrey School of Public Affairs.

It is easy to overlook the presence of women in our prison system. After all, in Minnesota, women account for just over 7% of the prison population, a mere 737 individuals.1 And the same is true across the country, with women comprising just 7% of the estimated 1.53 million people held in state and federal correctional facilities.2 Given these small numbers, the path to reducing mass incarceration is generally framed through its impacts on men. Fewer researchers work on questions such as whether the reasons women are imprisoned are unique, whether their rehabilitative needs are different, or whether the experience of prison impacts their outcomes differently than it does men.

In June, the Robina Institute of Criminal Law and Criminal Justice at the University of Minnesota hosted Women in Prison: Voices of Hope from Within Prison Walls. The event aimed to bring women’s unique challenges in imprisonment to the fore through dialog among researchers, practitioners, artists, and former inmates. Much of the discussion drew on participants’ expertise and experiences with Shakopee Correctional Facility, the sole women-only prison in Minnesota. Though several points were raised during the day-long discussion, two were particularly striking.

First, incarcerated women face a unique parenting struggle. Many women who are incarcerated have children, and many are the primary caregivers for those children. When a woman is imprisoned, if the father is not also a primary caregiver, the children must be placed with a relative or in foster care. Once an out-of-home placement occurs, the children’s “permanency clock” begins ticking. State and federal laws require close attention to this metric, designed to ensure that the best interests of the children are met by achieving a safe, stable, and permanent home as quickly as possible. In some cases, this means terminating parental rights. But as one panelist stated at the Robina event, “child protection timelines don’t work with prison timelines.”

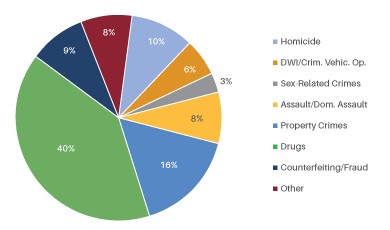

Figure 1. Active Sentences by Offense – Shakopee Correctional Facility

Source: Minnesota Department of Corrections, Daily Inmate Profile – Shakopee (08/14/2017).

One of the grounds for terminating an individual’s parental rights is abandonment,3 and while incarceration in and of itself is not sufficient to constitute abandonment, in order to maintain parental rights, incarcerated women must maintain a relationship with their children to the best of their ability through letters, cards, visits, and inquiries about the children’s welfare.4 But nearly two-thirds (61%) of the women currently incarcerated at Shakopee have been committed from outside of the seven-county metro area5 so the distances to the homes from which the women came may be too great for relatives to travel. As a result, most incarcerated women in Minnesota are unable to receive visits from their children; cards, letters, and perhaps an occasional phone call are their only available means to maintain or restore a relationship. Additionally, the majority of women incarcerated at Shakopee are there for drug offenses (Figure 1) which adds an additional layer of difficulty. Many may be struggling to overcome addiction, and while they are engaging in recovery, it may be difficult to simultaneously work on family relationships. Yet failure to show progress toward overcoming addiction may harm their chances of reuniting with their children upon release.

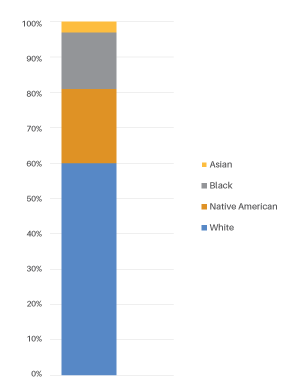

Second, the incarceration rate of Native American women in Minnesota is significantly higher than other groups. At Shakopee, Native American women comprise 21% of the inmate population (Figure 2). Though individuals of all non-white races are over-represented in Minnesota’s prison population, the incarceration of Native Americans is dramatically disproportionate—Native Americans of all genders make up only about 1% of the Minnesota population.6 And the proportion of Native American women in the prison population outpaces that of men. In most facilities for male offenders, the percentage of men who are Native American hovers around 9 to 11%. Only at Oak Park Heights – Minnesota’s maximum security prison – do the numbers begin to approach the proportions seen at Shakopee, with 16% of the population there reported as Native American.

Figure 2. Population by Race – Shakopee Correctional Facility

Source: Minnesota Department of Corrections, Daily Inmate Profile – Shakopee (08/14/2017).

These disparities are not unique to Minnesota. Native Americans represent 23% of the prison population in Montana, 19% in North Dakota, and 29% in South Dakota.7 Panelist Autumn Cavender-Wilson attributed the disparity in Minnesota to the inter-generational effects of historical trauma. Judge Bruce Peterson discussed the need for culturally specific services, but it was noted that, given the number of Native American Nations, each with its own traditions and identities, it is difficult to ensure placement in a program that speaks appropriately to each Native American individual’s identity. Regardless of the reason for or challenges created by the disparity, far more work remains in uncovering and addressing the root causes of racially disproportionate incarceration of Native Americans in Minnesota and nationally.

Our participants raised other issues that also deserve attention and study. Like prisons around the country, Shakopee is well over capacity. And many women who are incarcerated have significant trauma in their pasts, raising questions about how we can better identify and treat such trauma before it results in criminal outcomes. Studying and developing policy solutions tailored to the unique issues of women in prison may not be attractive—it is unlikely that these actions would generate immediate, large-scale impact in the way that male-focused solutions might. But just as there is no magic bullet that will end and reverse mass incarceration, there is no limit to the power of an accumulation of multiple, small-scale solutions to targeted issues.

View the video of the Robina Institute’s In Conversation Women in Prison in Minnesota below.

- 1Minnesota Department of Corrections, Adult Prison Population Summary (07/01/2017).

- 2Bureau of Justice Statistics, Prisoners in 2015 (Dec. 2016).

- 3Minn. Stat. § 260C.301, subd. 1(b)(1) (2016).

- 4See In re Children of Wildley, 669 N.W.2d 408 (Minn. Ct. App. 2008).

- 5Minnesota Department of Corrections, Daily Inmate Profile – Shakopee (08/14/2017).

- 6Minnesota State Demographic Center website, Featured Data, Minnesota’s Statewide Population by Race and Ethnicity 2000-2015.

- 7Bureau of Justice Statistics, Prisoners in 2015, Appendix Table 3 (Dec. 2016).