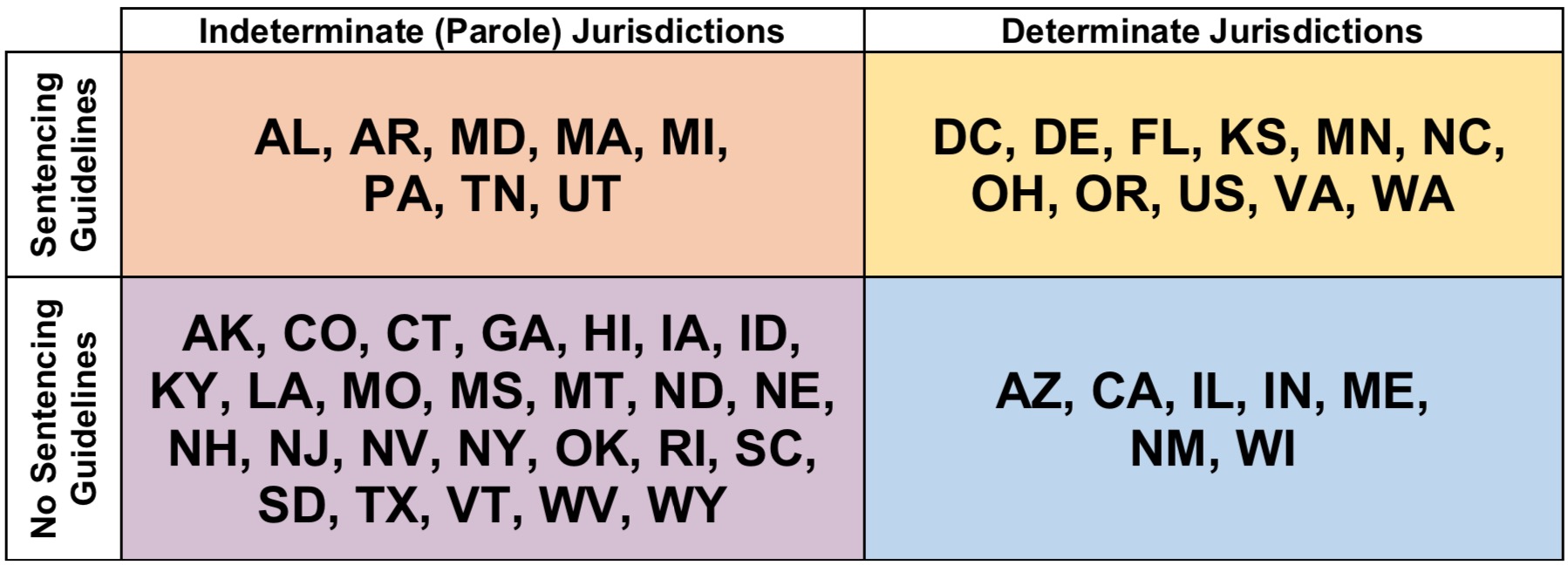

This article focuses on jurisdictions that have sentencing guidelines for judges on the “front end” of the punishment process but have also retained discretionary parole systems for the release of prisoners on the “back end.” As of this writing, there are eleven sentencing guidelines jurisdictions that have abolished discretionary parole. The remaining eight jurisdictions – Alabama, Arkansas, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and Utah – have retained discretionary parole release for most or all offenders serving felony sentences.

Background: The Relationship Between Sentencing Guidelines and Parole

At one time in the United States, most jurisdictions had discretionary parole release. In 1976, Maine was the first state to abolish parole, followed by Illinois in 1978 and Minnesota in 1982.[1] As of 2017, 16 states have abolished discretionary release.[2] Parole abolition was part of a movement towards “determinate” (fixed term) sentencing wherein policymakers focused on greater predictability in punishment.[3] In the early 1980s, those who favored parole abolition argued that American prisons were not capable of rehabilitating prisoners and that board decisions were arbitrary and not based on indicia of rehabilitation.[4] At the same time, the goal of incarceration shifted from rehabilitation to punishment.[5] Parole release, which had often been viewed as a safety valve against expansion of prisons, was also critiqued as ineffective (in part because some Boards rarely released prisoners).[6]

During the same period (beginning in the mid-1970’s) many states formed sentencing commissions; most of those commissions promulgated sentencing guidelines (see Timelines of Commissions and Guidelines). Sentencing guidelines created a systematic way to sentence similarly situated defendants based on offense severity and criminal history. Goals of the guidelines included setting rational and consistent standards, increasing proportionality and uniformity, and ensuring public safety (see What are Sentencing Guidelines? and Why Have U.S. State and Federal Jurisdictions Enacted Sentencing Guidelines?).

Table 1. Sentencing Guidelines and Parole in U.S. Jurisdictions

In some jurisdictions, adopting sentencing guidelines and abolishing parole went hand in hand. For example, Virginia’s 1994 crime bill abolished parole and created voluntary felony sentencing guidelines to address problems with violent crime and sentencing disparities. This reform was also designed to redirect non-violent offenders away from prisons. Under the new sentencing regime, Virginia’s offenders serve about 90% of their sentence, and guidelines sentence lengths are designed to be similar to the incarceration periods most offenders served when the state utilized parole release. Virginia policymakers claim that this shift (along with a national drop in crime rates) allowed them to curb their prison population and better meet several other correctional goals.[7]

The latest version of the Model Penal Code on sentencing has also taken the position that in an ideal guidelines-based system, parole should be abolished. This is based on a “preference for a determinate sentencing system over a system in which parole boards hold substantial authority to set actual lengths of prison terms.”[8] The authors give several reasons for this decision, including that the judiciary is better positioned to determine a proportionate sentence, that parole systems offer prisoners few procedural protections and offer little transparency in decision-making, that boards are too susceptible to political pressure, and that they have contributed to prison growth.[9]

However, in the eight jurisdictions (shown in upper left cell of Table 1), sentencing guidelines and discretionary parole release still operate simultaneously. In some of the jurisdictions, this means that both the sentencing judge on the “front end” and the parole board on the “back end” of the punishment process follow guidelines that help to determine the length of the sentence. In other states, there may be sentencing guidelines for judges at the “front end,” but no guidance for the parole board’s release decision on the “back end.”

A More Detailed Look at Indeterminate Sentencing in Guidelines States

As Table 2 shows, there is variation among the eight jurisdictions that have both sentencing guidelines and discretionary parole release. Five states have purely advisory sentencing guidelines, two have mandatory guidelines, and Alabama has both (for more details, see Varying Binding Effects of Guidelines).

In many states, judges use the guidelines to set the maximum term of sentence. The minimum term that must be served before the individual is eligible for release is then set either by statute or by the parole board. In some states, however, the guidelines also dictate the relationship between the minimum and maximum term. For example, in Arkansas, for cases in which the guidelines apply, judges consult the sentencing grid to set the maximum term. The same grid establishes whether the minimum term that must be served before eligibility for parole will be 50% of the maximum term or some lesser percentage based upon the severity of the offense.[10] In Massachusetts, judges who choose to follow the advisory guidelines must set the minimum term at 2/3 of the maximum.[11]

In Michigan and Pennsylvania, judges instead use the guidelines to set the minimum term. In Michigan, the maximum term is always the statutory maximum for first-time offenses but may vary for repeat offenses.[12] In Pennsylvania, the law requires that the maximum be no more than twice the minimum, and in practice, the maximum term is always double the minimum term.[13]

Utah takes an entirely unique approach. The guidelines serve to guide the sentencing judge on the disposition (i.e. prison versus probation), but if the judge pronounces a prison disposition, the pronounced length of incarceration will equal the indeterminate range defined in statute (e.g., for a second-degree felony, the law provides for a sentence of 1 to 15 years) rather than the term stated on the grid.[14] The duration on the grid, which falls within the statutory range, merely represents the typical time served for that offense, and serves as a recommended duration for the Board of Pardons and Parole.[15]

Four states currently have parole guidelines in addition to sentencing guidelines. These guidelines inform when the inmates who have become eligible for release are actually allowed back into the community. In Michigan, the guidelines are set by the Department of Corrections and the Board may not depart from them except for substantial and compelling reasons, stated in writing.[16] As noted above, in Utah the sentencing guidelines provide direction for both the sentencing court and the parole board. The Board is “encouraged” to comply with the guidelines, which set forth the typical time served based on the seriousness of the offense and the criminal history of the offender.[17] In Alabama and Maryland, the guidelines are developed by the parole board. In Alabama, the guidelines are in a preliminary phase of development, and are merely one of many factors the parole board can use in determining release.[18] In Maryland, the parole guidelines take into account the current sentence and the inmate’s risk level; they are also advisory.[19] Pennsylvania’s sentencing commission is mandated to produce parole guidelines but has not yet done so. If developed, they would be advisory.[20]