At the end of 2016, more than 4.5 million (or 1 in 55) U.S. adults were on community supervision, compared with 2.2 million incarcerated. Over 80% of adults under community supervision are on probation (or court-ordered community supervision for a misdemeanor or felony-level offense) and the remainder are on parole (or community supervision following a stay in prison). Many of these adults cycle through jails and prisons: in 2017, roughly half of all annual prison admissions were for probation and parole revocations. This “churn” increases the risk of infectious disease transmission, a risk that has grown exponentially with the spread of COVID-19. Media reports have already documented hundreds of positive test results for the novel coronavirus among people who are incarcerated and staff working in jails and prisons.

Adults on community supervision, like people who are incarcerated, have high levels of chronic illness that make them susceptible to complications from COVID-19. In a recent article in the Journal of Correctional Healthcare, our team used national survey data (from the 2015 and 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health) to estimate the prevalence of common chronic conditions among adults aged 18-64 years who had been on probation or parole in the past year.

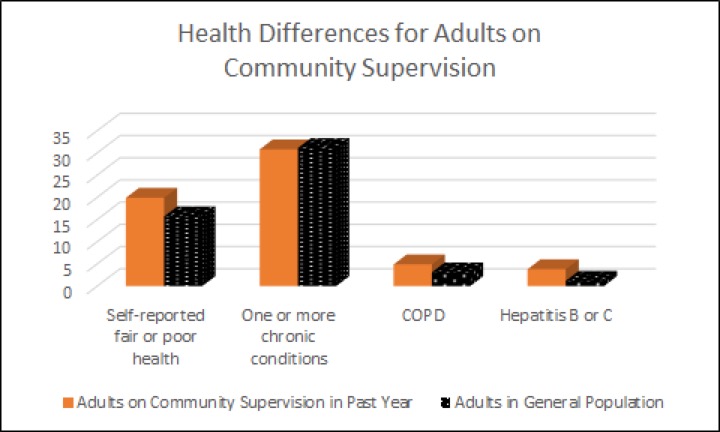

Compared to the general population, adults with recent experiences of community supervision were significantly more likely to report fair or poor health. They were equally likely as the general population to experience one or more chronic conditions, but were more likely to experience lung disease (or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD]) and hepatitis B or C--two diseases that put people at elevated health risks for COVID-19.

These differences emerge despite the fact that adults on probation and parole tend to be substantially younger than the general population. When we accounted for differences between the two groups in age and other sociodemographic characteristics, the differences in poor health and elevated rates of COPD and Hepatitis B or C persisted, while the presence of one or more chronic conditions emerged as being significantly more prevalent among adults on community supervision. Notably, these estimates exclude elderly (age 65+) adults on community supervision, who represent a small minority of the total population, but have more chronic conditions and face even higher risk of death from the novel coronavirus.

Although individuals on supervision disproportionately need healthcare services, they are less likely than the general population to have access to healthcare (though this gap narrowed with the Affordable Care Act). While the CARES Act provides COVID-19 related treatment for uninsured adults, it does not cover care for other medical needs. This means that adults on community supervision have limited access to care for management of their chronic conditions, which may increase their risk further during the COVID-19 pandemic. And while some probation and parole offices across the country are suspending in-person visits and technical violations (or returns to jail or prison), others continue with in-person check-ins and revocation policies that increase risk of contracting the virus. This risk is distributed not just to adults on probation and parole, but their families and neighborhoods. It also puts staff in criminal justice agencies at risk, including probation and parole officers, and their families and neighborhoods.

Many commentators on the pandemic have noted that it has exposed fundamental fault lines and vulnerabilities in U.S. society, including stark racial, ethnic, and income inequalities that impact access to healthcare, sick leave, housing, and more. Spotlighting the needs of justice-involved adults makes these inequities especially visible, as people from poor communities (and especially poor communities of color and Indigenous communities) are disproportionately criminalized and exposed to the risks of incarceration and community supervision.

Many public health and criminal justice officials, as well as reform advocates and civil rights leaders, have argued that we should substantially decarcerate jails and prisons during the current pandemic to limit the spread of COVID-19. But many of the people released will be placed on probation, parole, and other forms of monitoring (including house arrest and electronic surveillance). The burden of health conditions on these adults demonstrates the need for a healthcare system that is better integrated across sectors to ensure that individuals on community supervision are enrolled and maintained in health insurance programs that provide access to emergency and primary care. This means making sure that people do not lose public health insurance when incarcerated. It also means having healthcare providers who understand and can respond to the considerable challenges faced by individuals impacted by the justice system. Finally, for community corrections, it means going beyond shifting supervision practices to building partnerships with organizations and providers that can meet the health needs of adults on supervision.