This post is also published on The Crime Report.

Meek Mill, winner of the 2016 Billboard Music Award for Top Rap Album, made news in November when he was sentenced to two to four years in prison for violating probation. The judge cited a series of supervision violations as reasons for the revocation. They included testing positive for drug use, new arrests for low-level crimes (one for popping a “wheelie” on a dirtbike and one for a fight), and failure to abide by travel restrictions. He had no new criminal conviction.

Mill’s probation originally stemmed from a 2007 arrest, which came with a short stint in jail and a seven year probation term. His sentence sparked a wave of protest in Philadelphia and beyond, as his supporters push for the judge’s recusal and broader criminal justice reforms. This activism is joining an increasingly loud criminal justice chorus calling for reform. On Monday, a group of leading correctional administrators and advocates, including Van Jones and #Cut50, declared that the U.S. should cut probation and parole populations in half.

As Jay-Z wrote in the New York Times, Mill’s imprisonment sends the message that the criminal justice system “stalks black people.” What happened to Mill is not an exception. In fact, it’s just one example of a bloated criminal justice system which not only sends too many to prison, but also entraps more than 4.6 million adults on community supervision—with most serving their time on probation.

Probation is a court-ordered form of criminal justice supervision meted out for both felony and misdemeanor offenses. Unlike parole (which is typically supervision following release from prison), individuals can be sentenced directly to probation, for terms lasting up to more than 10 years in a handful of states.

Meek Mill’s story is typical in at least three respects:

- Young black men without a high school diploma face exceptionally high rates of probation supervision;

- The terms of supervision are frequently very difficult to meet for years on end and probationers are frequently imprisoned for violating the terms of supervision;

- Revocation rates are especially high for young African-American men.

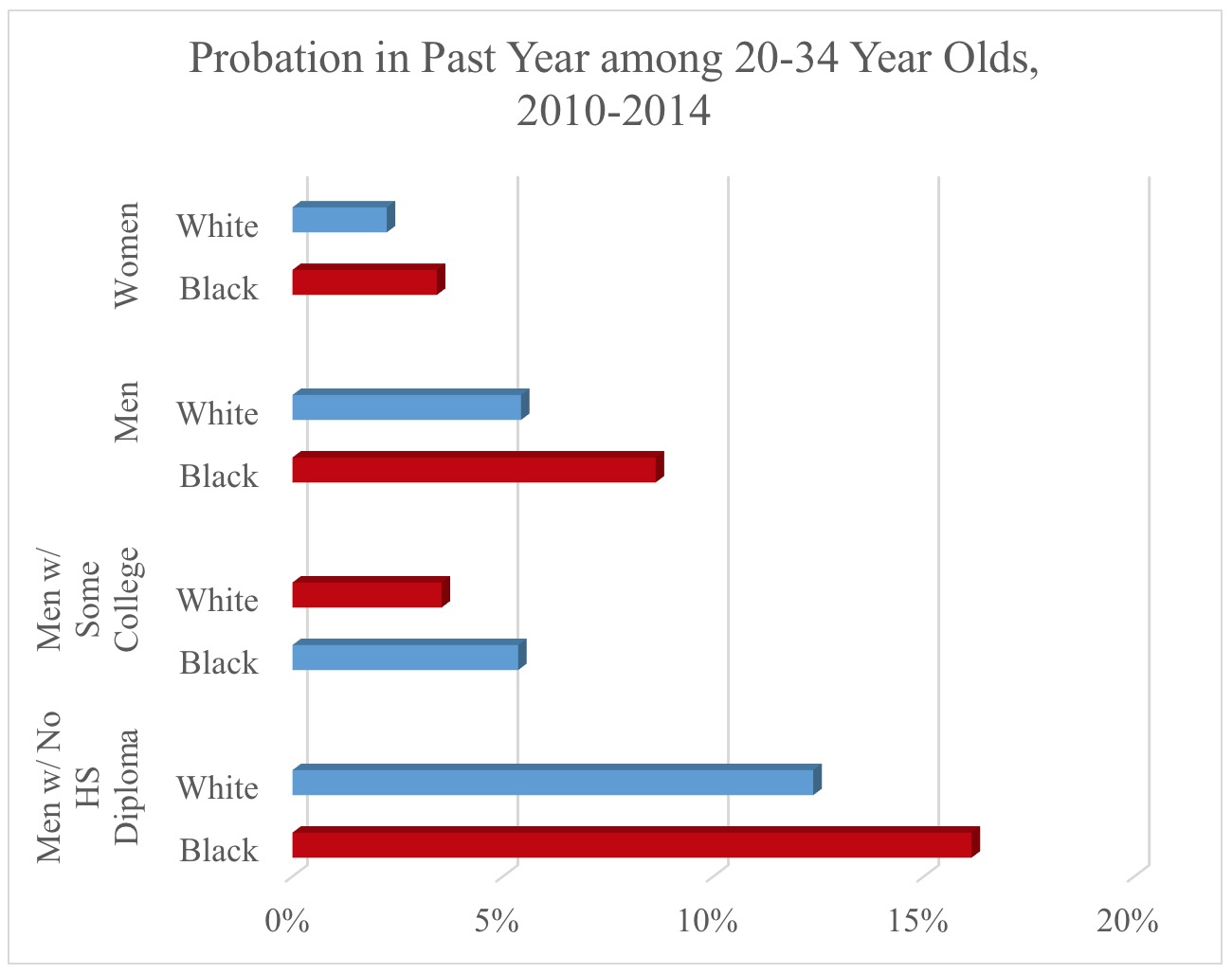

In recently published research, I use a household survey that collected data in 2010, 2011, 2012, and 2014 to show who is on probation. As compared to other Americans, those on probation are more likely to be young, African-American and Hispanic men with low levels of formal education. During this period, one in six black men aged 20-34 years without a high school diploma reported being on probation at some point during the year. For young white men who never graduated from high school, one in eight reported probation supervision.

Education (or the economic stability needed to enter college) protects men from probation; among young men with some college experience, an estimated four percent of white men and five percent of black men reported being on probation in the past year.

These racial disparities grow starker when we look at who is incarcerated for probation violations in jail and prison. While 57 percent of probationers in the community identify as non-Hispanic whites, only 40 percent of former probationers in jail and prison say the same. In addition, these former probationers make up a substantial share of the incarcerated population. Nationwide in the early 2000s, an estimated 33 percent of jail inmates and 23 percent of prison inmates were on probation at the time of their arrest.

Lastly, like Meek Mill, many of these adults in jail and prison are incarcerated for nothing more serious than a violation of the terms of their supervision. Nearly one in three jail inmates and one in 5 prison inmates who were on probation at arrest are incarcerated because of these “technical” violations, excluding new arrests.

As in Mill’s case, these supervision violations include failure to report and abide by travel restrictions, positive drug tests, and other low-level administrative failures. Another 32 percentof failed probationers in jail and 6 percent of those in prison are incarcerated for revocations related to new arrest charges, but have not been convicted of a new crime. Only 25 percent of failed probationers in jail (but 70 percent of failed probationers in prison) were there for a new criminal conviction.

This evidence suggests that the criminal justice system pushes an extraordinary number young men of color into community supervision—and then sets them up to fail by requiring an exacting performance that is nearly impossible for young men in high-crime and heavily-policed neighborhoods with few resources to meet. At the same time, probation provides few supportive services to help young adults succeed and exit supervision successfully.

As Columbia University’s Justice Lab recently declared, community corrections is “too big to succeed.” Signed by leading practitioners and policy reformers in the field, the report calls for a series of community supervision reforms that can be embraced by states and local jurisdictions, including:

- Cutting the overall supervision population in half, reserving supervision for only serious cases;

- Reducing the length of supervision;

- Limiting the number of conditions imposed on probationers (e.g., drug testing and travel restrictions);

- Incentivizing positive progress on probation by allowing early discharge;

- Eliminating probation supervision fees;

- Improving services and support for probationers.

If such principles had guided Philadelphia and Pennsylvania when Meek Mill was sentenced and supervised, he would likely not be behind bars today. By shrinking probation and parole, limiting supervision to only more serious cases, and providing more meaningful support and fewer barriers to success, jurisdictions can scale back the fiscal and social costs of mass punishment and improve the lives of millions of Americans.

Michelle S. Phelps is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at the University of Minnesota. Her research is on policing, prisons, and probation.