In May of 2016, Robina Institute Faculty Affiliate and Probation Revocation project advisory board member Michelle S. Phelps published new research on Mass Probation in the U.S. in the journal Punishment & Society. This project was funded in part by the Robina Institute.

As highlighted by recent reports from the Robina Institute, the U.S. is “exceptional” not just for its massive prison population, but also for its rates of probation and parole supervision, which are more than four times the average rate across European countries. Both of these forms of community supervision allow individuals to serve their sentences in their home communities under the supervision of a probation or parole officer. Probationers and parolees are required to abide by a set of conditions, typically including regular reporting, avoiding new arrests, paying fines and fees, abstaining from drug and alcohol use, participating in programs, and finding or maintaining employment. Failure to meet these conditions may result in supervision violations, which can end with revocation to jail or prison.

The article, entitled “Mass Probation: Toward a More Robust Theory of State Variation in Punishment,” defines the term mass probation and explains state-level variation. As with mass incarceration, mass probation is characterized both by its historically and internationally unprecedented scale and its social concentration. Between 1980 and its peak in 2007, the state and federal probation population reported to the Bureau of Justice Statistics grew from 1 million to over 4.2 million. Using population data from the census, this translates into an overall prevalence rate of 1 in 53 U.S. adults in 2007. For black Americans, this rate rises to 1 in every 21 adults who were on probation at the end of the year—and for black men the rate rises even higher (to 1 in 12). Thus, for black men in particular, probation supervision has become a frequent life course event.

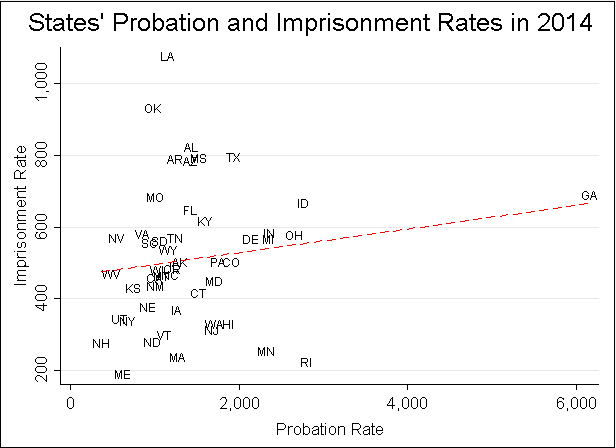

However, not all states equally embraced mass probation. Just as the U.S. is exceptional compared to other Western industrialized nations, so too are some U.S. states exceptional in terms of their probation supervision rates. State probation supervision rates reported to the Bureau of Justice Statistics in 2014 range from a low of 370 per 100,000 adults (or 1 in 272) in New Hampshire to a high of 6,160 (1 in 16) in Georgia. Yet this variation does not simply map onto state-level differences in punitiveness as measured by incarceration rates. As the figure below demonstrates, states’ imprisonment and probation rates are only weakly correlated.

Sources: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Probation and Parole in the United States, 2014; Bureau of Justice Statistics, Prisoners in 2014.

Notes: Prisoner counts represent the total number under the state’s jurisdiction sentenced to 1 year or more. Probationer counts represent the total number reported as under supervision by adult probation authorities. Rates are calculated per 100,000 adults in the population.

Most notable in this figure are states like Louisiana and Oklahoma, which have relatively low probation rates but very high imprisonment rates, and Minnesota and Rhode Island, which show the reverse trend. Also clear is the truly exceptional scale of probation supervision in Georgia.

How do we explain these divergences? The article evaluates several explanations for these patterns. The results show that states’ probation and imprisonment rates decoupled during the carceral build-up, driven in part by novel trends in imprisonment and probation across states. While some states expanded both forms of supervision, others came to specialize in probation or imprisonment.

However, the results also reveal that the divergence is in part due to the systematic under-reporting of probationers among some high-imprisonment states. This suggests that the official number of probationers in the U.S. may be an under-count of the relevant population. States like Georgia then may be exceptional not just for their high rates of control, but their more complete reporting of the probationer population. In some states, probationers may be supervised by state, local, and private agencies, complicating data collection. The article concludes by calling for more diverse research on the expansion of mass probation.

Read more about Professor Phelps' media interviews, resources, and other writing.