Over the past half-century, researchers have focused considerable attention on the causes and consequences of mass incarceration. One of those consequences is increased health disparities due to the experience of imprisonment. Yet the majority of the criminal justice population is not currently behind bars, but supervised in the community, most often through probation. Minnesota is a leading exemplar of this pattern: In 2018, Minnesota had the sixth-lowest incarceration rate in the nation, but the fifth-highest community supervision rate. Yet, the question of how probation intersects with individual and community health, health care access, and health disparities has been largely neglected by researchers.

In 2017, our team came together to study this intersection, using Hennepin County, MN, as a strategic case study. Hennepin represents the largest county and probation department in the state and is a leader in integrating health and social services programs for county residents. Our project brought together an interdisciplinary group of researchers from the University of Minnesota--with expertise in criminology, law, medicine, public health, and family systems--with Hennepin Healthcare and Hennepin County’s Department of Community Corrections and Rehabilitation (DOCCR) to analyze these intersections.

In this post, we reflect on the lessons learned from over four years of collaboration and the questions we bring with us into our work in the future. In short, we found important points of connection between community supervision and health care systems, especially the need to better support the health of people with criminal justice contact. However, we also found illustrative points of tension between the two systems--which we use to conclude the post with a series of questions for future research.

Research Questions

When we submitted the grant for this project back in summer 2017, we proposed to investigate three core research questions:

1) What are the health conditions, health care use patterns, health insurance rates, and treatment rates among individuals on community supervision?

2) How does health impact one’s ability to complete terms of community supervision and how do the conditions of community supervision impact one’s health and wellbeing?

3) To what extent do disparities in the health care and criminal justice systems overlap and contribute to poor outcomes for racial and ethnic minorities in Minnesota?

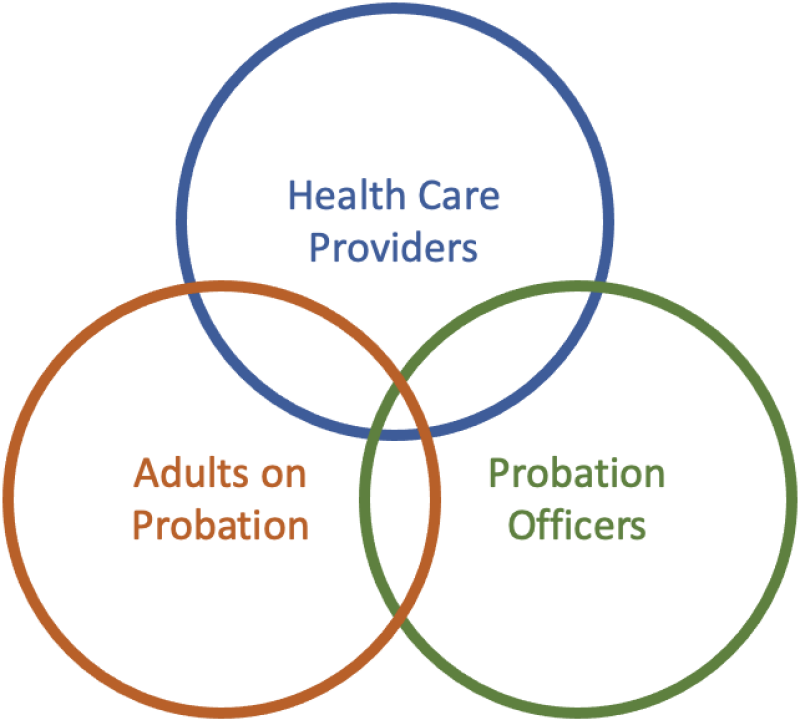

To answer these questions, we split into four teams, organized by data collection efforts. One team focused on collecting, linking, and analyzing administrative data from the county and state for two cohorts of people on probation (all adults supervised by DOCCR in 2014 and 2016), estimating the prevalence of specific health conditions and health care use rates of various county services. A second team conducted qualitative interviews with 23 health care providers to understand how the health system was responding to people with criminal justice contact. The third team interviewed 166 adults on probation, asking about their health, but also broader life experiences and circumstances. A final team conducted a survey with 55 probation officers (POs) to map what officers know about the health of their clients and how they respond to various kinds of supervision violations.

As we worked on reports and papers from the project, we started to see how our choice of data collection shaped the kinds of questions we answered. Instead of the two-way relationships mapped in the original diagram, we started to map the relationships and tensions between groups of people working and living at this intersection, from people on probation to their POs and health care providers. We came to see our work better symbolized as a venn diagram of actors. In this post, we provide a brief summary of our findings at each of these points of overlapping circles.

Adults on Probation & Health Care

Our earliest work focused on understanding the health conditions and health care utilization patterns of two cohorts of adults on probation in Hennepin County. Merging DOCCR data with state-level health care claims records, we were able to analyze use of health care services for adults on probation enrolled in Medicaid. Compared to the general population, adults on probation were disproportionately male (80.5%), young (mean age: 35.5 years), and Black or African American (52.9%). Compared with the general population, the probation cohorts showed elevated rates of substance use disorders (66.5% vs 8.1%), mental illness (55.3% vs 14.4%), and common chronic physical conditions (e.g. asthma: 17.0% vs 12.5%, chronic kidney disease: 5.8% vs 0.2%).

Our interviews with adults on probation confirmed these findings and extended our discussion into the lived experiences of people on supervision. Drawing on our non-random sample of 166 adults on probation (recruited via flyers posted in DOCCR offices), we found that over 90% reported ever being diagnosed with one or more health conditions, with the majority of diagnosed conditions being mental health conditions (72%), followed closely by physical health conditions (67%). The five most common conditions included depression (64%), other mental health conditions (55%), chronic back pain (29%), asthma (25%), and hypertension (25%). In addition, 75% reported that before starting their current term on probation, drug or alcohol use had been a problem for them.

Compounding these health challenges was a lack of health insurance coverage. Just under half of our interviews (40%) reported being uninsured or experiencing gaps in health insurance coverage. Given the racial disparities in who is exposed to probation, this under-insurance of the population suggests important racial equity concerns. Despite low insurance rates, the majority of respondents reported using both medical (83%) and mental health (58%) services at least once in the past year. In addition, 64% of participants reported participating in substance use treatment since starting probation.

The health care providers we interviewed were well aware of the challenges facing adults with criminal justice system contact. We selectively invited physicians from three community-based clinics that provide health care services for underserved populations in Hennepin County to participate, interviewing 23 providers in internal medicine, psychiatry, family medicine, and emergency medicine. Health care providers discussed the many health burdens faced by people with criminal legal system contact, including how their conditions were often exacerbated during periods of incarceration.

Providers often expressed uncertainty and ambivalence about when and how to address a patient’s criminal legal system involvement. While acknowledging that there were key ways in which incarceration contributed to discontinuity of care, providers questioned when and how to probe for this information sensitively. In addition, they expressed ambivalence about their role in probation supervision and, as we describe below, hesitancy about interfacing with patients’ POs. At the same time, some physicians discussed how knowing about a patient’s past or potential future incarceration could play a significant role in informing the physician’s care plan for the patient. For example, a physician may make a different recommendation about a specific course of treatment for opioid use disorder if they know that a patient is likely to be incarcerated and medication-assisted treatment is unlikely to be maintained. This consideration of the limits of correctional policy had important implications for the quality of care adults with system contact received in the community.

Clients & POs

In interviews with adults on probation, we found that the vast majority (roughly 90%) of participants agreed that their PO(s) treated them fairly and with respect. Three-quarters of our sample reported that they receive support from their probation officers when needed and that probation had been “somewhat helpful,” “helpful,” or “very helpful.” At the same time, however, over half of participants (58%) agreed or strongly agreed that their experience on probation had been stressful.

We understand this ambivalence through the lens of coercive care. Probation--and supervision through POs--was experienced most positively when clients felt their PO cared and meaningfully assisted them in meeting their needs, including food and housing insecurity, health care and treatment programs, and economic opportunities. Yet POs primary “tool” to change clients’ behavior and enforce mandated conditions was revocation--or the removal of the person from their home and community for a violation of supervision. This power to file a revocation motion loomed large in clients’ perceptions of POs, with participants fearing incarceration and the separation from family members (including minor children), other loved ones, and employment and housing supports.

Experiences on supervision were connected to participants’ health needs. Revocation fears were higher among those with poor physical and mental health and continued substance use disorders. In addition, while 55% of participants described their health as improving while on probation, 20% described their health as deteriorating over probation. For these participants, the most common description of the impact of probation on their health was that supervision had worsened their mental health, adding stress and burdens to already precarious lives. In some cases, this stress was racialized. For example, for people from families and neighborhoods that were aggressively policed and faced high levels of criminalization, the prohibition on “associating with known felons” was experienced as a deeply unjust stressor.

For many adults on probation, the coercive care of probation revolved around substance use or sobriety and drug testing. When probation was experienced as helpful and health-improving, it was often because participants felt that their arrest and supervision had helped them get treatment for substance use disorders and to achieve and maintain sobriety. Conversely, however, much of the daily stress of supervision revolved around frequent and intrusive drug tests. For those still using illicit substances, the testing involved navigating the potential for revocation; for those who were sober, the test sometimes represented a demanding intrusion into their ability to find and maintain employment and meet the other demands of their lives. For still others, this emphasis on substance use and drug testing and treatment misunderstood the challenges that had fueled their arrest and provided little help in supporting their desistance from crime.

The mixed messages adults on probation received about violations and revocations were echoed by our survey with POs. Recruited via emails sent to all POs supervising probation clients in Hennepin County, 55 POs completed our online survey. POs understood their clients’ health needs: Nearly two-thirds of probation officers rated the health of people on probation as being worse than the general public, while about one-third rated probationer health as being about the same as the general public. Probation officers perceived that people on probation experienced a cycle in which lack of financial resources, health insurance barriers, and time and transportation limitations resulted in people having less access to preventive care (or care in general), which worsened their health and necessitated more emergency room visits. In addition, 60% saw depression as a moderate to extreme barrier to clients’ improved health.

Probation officers reported that knowledge of their clients’ health issues was essential to their ability to effectively supervise, yet they were less confident or consistent in how to reply to violations related to health conditions and behaviors. In a series of vignettes about non-compliance with probation conditions related to mental health, drug use, and physical health, probation officers tended to respond with options that paired increased supervision along with low-level interventions such as a problem-solving discussion about ways to get into compliance. A significant share of POs, however, replied that they may take clients to court or threaten jail.

For example, in a vignette where the person on probation was not taking their prescription medication and missed three mental health appointments, 40% of responding POs said they would “threaten incarceration” as a likely response to that violation. Similarly, 36% of POs said they would respond with such a threat in response to a client who missed two drug tests and a probation meeting and then tested positive at a later visit. These findings show that while POs were explicitly committed to helping clients address their health needs (particularly drug treatment), they also actively deployed the threat of incarceration for motivating compliance. Clients’ fears of revocation were thus a rational response to these threats.

POs & Providers

As described above, POs questioned how to respond to violations related to health behaviors. In addition, they experienced frustration with communication with health care providers. Nearly all probation officers indicated that having information about a person’s attendance, progress, and completion of treatment programs was very important to their ability to provide effective supervision. However, most probation officers also indicated that they had to actively seek out information about a person’s progress in a treatment program. Probation officers felt that treatment providers would usually provide information upon request, but that HIPAA and other patient privacy concerns, heavy workloads, and a lack of understanding about probation or the role of probation officers sometimes prevented information sharing. From the point of view of POs, these limits on information sharing made their job of compliance enforcement more difficult.

Health care providers also reflected on these tensions. One of the issues physicians discussed was communication with POs. Most physicians noted that it was uncommon to hear directly from POs, but that when they were contacted, physicians were very limited in what they could share. While some providers heard from patients a desire to share information with their PO about their health status (e.g., improved mental health or medication compliance), physicians understood other patients to be understandably hesitant about what could be disclosed to their PO for fear of violations (e.g., substance use). As a result, many providers worked to shield their patients, when possible, from negative legal system repercussions. This motivation partly underlyed why POs were frustrated in trying to gain information from health providers.

Lessons Learned

As we near the end of this project, we realize we have more fully answered some of our initial research questions than others. We know more about the health and health care access of adults on probation in Hennepin County. But our findings about how to improve health, health care access, and supervision outcomes, and redress racial disparities, are more tentative.

In the project reports, we trace a number of policy recommendations to better support the health and wellbeing of people under supervision, while also minimizing the harms of probation. These include limiting drug testing and revocations for technical violations of supervision and increasing residents’ access to and take-up of health care and social services. This shift might also include giving POs more tools to change behavior beyond the threat of revocation, including incentives like early release from supervision for progress toward clients’ goals.

Our goal ultimately with this project was to identify when, where, and how health care and probation systems interplay in the lives of US adults. In the end, our conversations focused on not only the interconnections between health and probation systems, but also the ways these institutions are unique and should maintain separation. The goal should not be to introduce criminal justice actors further into the health care system. There are important legal, medical, and ethical reasons to defer to health care providers for making medical decisions with their patients. Yet, when conditions like substance use disorders are understood as both a health condition and criminal offense, these systems will necessarily intertwine as the state tasks POs with monitoring compliance with probation conditions. In addition, these kinds of criminogenic and health-related needs are rarely experienced in isolation, but instead are deeply intertwined with other forms of instability, including limited economic opportunities, housing crises, and more, which may over time serve to reinforce disparities in health and the criminal legal system.

We conclude then with a series of new questions and provocations:

-

What should the connections (and firewalls) between clients and staff members of the probation and health systems look like? In other words, how and for what purposes should health information be used by POs and how and for what purposes should criminal justice involvement be used by healthcare providers?

-

How should judges, departments, and probation officers balance the demands of care and coercion in setting the conditions, incentives, and punishment in supervision?

-

What should the relative size (and funding) of health and criminal justice systems look like to achieve the most benefit for the safety of low-income communities?

-

How can we better address the “social determinants of health,” or the root causes of many health disparities and crime outside, to preempt poor health and criminal legal system contact?

Answering these questions will ultimately help us to develop more effective interventions to build thriving families and communities.

Still Curious?

To learn more, please visit our website, where we list all of the project publications, including recent reports, policy briefs, and academic publications.

We will be updating this page with additional publications as they become available.